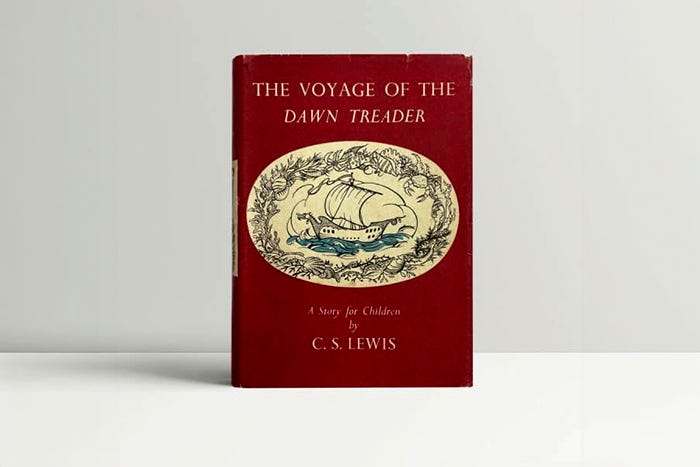

Welcome to our fall C.S. Lewis read-along. For the next few months, we’ll be going chapter by chapter through The Voyage of the Dawn Treader.

I want to give you inspiration and application of each book (and each chapter). What was going on in C.S. Lewis’ life as he wrote? What works and events contributed to the series? What ideas were Lewis trying to “sneak past the watchful dragons” of the reader? What can we draw from the books for our own lives?

If you’d like to catch up, you can see the full collection of articles from the previous two Narnia books. I’ve unlocked both of these posts for everyone, but again only paid subscribers will be able to view the chapter-specific articles.

If you’re wondering why The Voyage of the Dawn Treader is numbered “Book 5” by the publishers but we’re reading it third, you can read this explanation for the correct reading order.

Let the voyage begin!

Background of The Voyage of the Dawn Treader

C.S. Lewis finished The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, his third Narnia book, in just three months.1 But like almost every Lewis work, the roots go back much deeper, and these stretch across the Irish Sea.

Despite Lewis’ parents being well-read and filling their house with books, they didn’t enjoy the same types of stories as their sons and didn’t read to them. “Neither had ever listened for the horns of elfland,” Lewis says in Surprised by Joy. Instead, it was his nursemaid Lizzie Endicott who read to the young C.S. and Warren Lewis and told them bedtime stories.

While Endicott was only his nurse for three years, Lewis devotes a brief but heartfelt mention of her in Surprised by Joy, describing her as “nothing but kindness, gaiety, and good sense.” Along with his brother, Lewis says she was one of the two blessings he began life with.

Endicott filled the boys’ early childhood with fairy stories and Irish folklore.2 One popular type of old Irish story is an immram, which involves a hero traveling across the sea to the “Otherworld.” A particularly important immram in Irish culture and to Lewis’ development of Dawn Treader was The Voyage of Saint Brendan.

C.S. Lewis’ nurse Lizzie Endicott first introduced him to fantasy worlds, fairy stories, and Irish folklore.

During the journey, Saint Brendan traveled to various islands, one of which had a seemingly uninhabited mansion, endured a terrible storm, faced a sea monster, heard white birds singing with human voices, met a man with long white hair and beard covering his body, and lived off water without a need for food. If you’ve already finished The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, those ideas should sound familiar.

But in addition to his childhood nursery, Lewis was also drawing from the library within his mind. If you’re familiar with Greek classics, Lewis’ seafaring Narnia tale should evoke Homer’s Odyssey. Lewis specifically noted this story was drawing from Odyssey and St. Brendan.

If you know your British Romantic poets,3 you may recognize elements of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. Bible readers will also note parallels to John’s Gospel.

To this mix of literary experiences, Lewis brought his own mental pictures that often flittered through his mind until he found a home for them. He famously said The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe began with the picture of a faun carrying packages on a snowy day. Due to the episodic nature of Dawn Treader, Lewis may have had numerous images that were included in the voyage. In his notes during the book’s development, he calls it a “very green and pearly story.”

Pieces of what became the third Narnia book were part of Lewis’ attempt to find the second story. After Wardrobe, he first began what became known as the Lefay Fragment, which had elements reminiscent of The Magician’s Nephew. He also started another story that included a magic painting and a ship sailing to various islands, pieces of the eventual Dawn Treader. For a time, Lewis put those to the side and finished Prince Caspian.

The idea of saving images and pieces of writing for a later project is undoubtedly part of what allowed Lewis to be so efficient, turning around the entire Narnia series in a few years. In fact, that was part of his response to a young American schoolgirl who wrote asking for writing advice. He said:

When you give up a bit of work don’t (unless it is hopelessly bad) throw it away. Put it in a drawer. It may come in useful later. Much of my best work, or what I think my best, is the re-writing of things begun and abandoned years earlier.

We see that happen repeatedly in the Narnia series, including here in The Voyage of the Dawn Treader.

Lewis would need all the childhood stories, expansive reading, and mental images to complete many of his Narnia books during what was a difficult season, both personally and professionally.

As we discussed in the Prince Caspian introduction, he was hospitalized for exhaustion in June 1949 after spending so much of his time teaching at Oxford, writing, and taking care of an increasingly sick and hostile Mrs. Moore. He booked a vacation back to Ireland on doctor’s orders, but Warnie had another drinking binge and took the trip instead to stay at a rehabilitation center.

Additionally, the friendship with J.R.R. Tolkien and the Inklings that had given him so much life was beginning to fade. Though some friends still gathered on Tuesday mornings, the last Thursday evening meeting of the Inklings happened in October. In his diary on October 27, 1949, Warren Lewis wrote, “Nobody came.”

Despite deep professional and personal stress, C.S. Lewis finished The Voyage of the Dawn Treader in three months, with most of the writing happening during the 1949 Christmas break

Still, Lewis finished The Voyage of the Dawn Treader in three months, with most of the writing happening during the 1949 Christmas break at Oxford. In September, he wrote that he had another idea for a children’s story. He was currently writing Prince Caspian, so this idea was undoubtedly Dawn Treader. He finished Caspian that fall, turned to Dawn Treader, and had a manuscript ready for his friend Roger Lancelyn Green to read in February 1950. The book was published in September 1952.

Reviews were generally positive. “The strange symbolism will not often be understood,” wrote Louise Bechtel in The New York Herald Tribune Book Review, “but it is well worth that place at the back of the child’s mind where it will linger until suddenly it’s clear.” In The New York Times Book Review, Chad Walsh, who later became a friend of Lewis’, said it was not quite up to the “very high level of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe,” but was better than Prince Caspian. The review in The New Yorker concluded it was “a juvenile odyssey that in excitement and beauty surpasses even the preceding volumes.”

Foreground of The Voyage of the Dawn Treader

In his previous Narnia books, Lewis gives a “supposal” working through what the “crucifixion and resurrection” (The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe) and the “restoration of the true religion after a corruption” (Prince Caspian) might look like in a world of talking animals. With The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, we move into the Christian walk. The ship’s journey reflects the faith journey of following Jesus.

“The whole Narnian story is about Christ,” C.S. Lewis wrote to a young reader in 1961. He explained to Anne Jenkins just how Jesus is imaged in the seven books. The Voyage of the Dawn Treader was about “the spiritual life (especially Reepicheep).”

Reepicheep captivated readers from the beginning. In his letters, Lewis repeatedly thanked children for their drawings of the chivalrous mouse. In our recent Narnia Madness tournament, Reepicheep finished second only to Lucy. While Reep was certainly a featured side character in Prince Caspian, he takes center stage and progresses as a character in Dawn Treader. If we want to draw lessons and spiritual life applications from this book, it’s best we keep Reepicheep in focus.

“The whole Narnian story is about Christ.” — C.S. Lewis

Think back to the last chapter of Prince Caspian. Reepicheep says that “a tail is the honor and glory of a mouse.” Aslan slightly chastises him by replying, “I have sometimes wondered, friend, whether you do not think too much about your honor.” While the sense of honor and glory remain, Reepicheep has embraced a newfound humility and purpose on board the Dawn Treader.

Due to words spoken over him in his nursery,4 Reepicheep is focused on reaching the “utter East” and Aslan’s country. During his journey, he will encounter wondrous glories and terrifying horrors, he will display seemingly irrational courage and timely wisdom, he will deepen old friendships and make new ones, but through it all, Reepicheep remains pointed to Aslan’s country. Nothing can deter him from that path. As a result, Lewis told a fifth-grade class in Maryland that “anyone in our world who devotes his whole life to seeking Heaven will be like Reepicheep.”

In Mere Christianity, Lewis argues that a heavenly aim is for an earthly benefit.

If you read history, you will find that the Christians who did most for the present world were just those who thought most of the next. The Apostles themselves, who set on foot the conversion of the Roman Empire, the great men who built up the Middle Ages, the English Evangelicals who abolished the Slave Trade, all left their mark on Earth, precisely because their minds were occupied with Heaven. It is since Christians have largely ceased to think of the other world that they have become so ineffective in this. Aim at Heaven and you get Earth “thrown in,” aim at Earth and you will get neither.”

As we follow the Dawn Treader’s voyage across the Narnian seas, may we gain a better bearing for our compass. Hopefully, we will be reminded to appreciate the various adventures and relationships this world offers but always keep our heading pointed toward Heaven. I’m excited to travel this voyage with you.

Next time: Chapter 1, “The Picture in the Bedroom”

Further up and further in

Resources used:

The Voyage of the Dawn Treader — C.S. Lewis

Prince Caspian — C.S. Lewis

The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe — C.S. Lewis

The Magician’s Nephew — C.S. Lewis

Surprised by Joy — C.S. Lewis

Mere Christianity — C.S. Lewis

The Collected Letters of C.S. Lewis, Volume 3: Narnia, Cambridge, and Joy, 1950-1963 — Editor: Walter Hooper

C.S. Lewis: The Companion and Guide — Walter Hooper

Past Watchful Dragons: The Origin, Interpretation, and Appreciation of the Chronicles of Narnia — Walter Hooper

Companion to Narnia: A Complete Guide to the Magical World of C.S. Lewis’ The Chronicles of Narnia — Paul Ford

Inside The Voyage of the Dawn Treader: A Guide to Exploring the Journey Beyond Narnia — Devin Brown

Into the Wardrobe: C.S. Lewis and the Narnia Chronicles — David C. Downing

Planet Narnia: The Seven Heavens in the Imagination of C.S. Lewis — Michael Ward

The Narnia Code: C.S. Lewis and the Secret of the Seven Heavens — Michael Ward

Becoming C.S. Lewis: A Biography of Young Jack Lewis — Harry Lee Poe

The Completion of C.S. Lewis: From War to Joy (1945-1963) — Harry Lee Poe

C.S. Lewis: A Life — Alister McGrath

The Fellowship: The Literary Lives of the Inklings — Philip and Carol Zaleski

The C.S. Lewis Readers’ Encyclopedia — Editors: Jeffrey Schultz, John G. West, Jr.

“The Nurse of Elfland: Lizzie Endicott and C.S. Lewis” — Reggie Weems, Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 41: No. 1, Article 14.

Wade Center Podcast “Into Narnia, Vol. 3, The Voyage of the Dawn Treader” — Marion E. Wade Center, Wheaton College

One can imagine, much to the chagrin of J.R.R. Tolkien

Once, Lewis was so convinced by one of Endicott’s stories of leprechauns and buried treasure that he convinced Warren to help him dig for it in their driveway. Unfortunately, the treasureless hole remained until their father came home at night and fell into it. After bearing most of the anger, Warren later wrote that “gold mining is an activity which I have left severely alone ever since.”

And had the same high school English teacher as me

There again is Lewis’ fondness for his nursery time and all things related to his nurse Lizzie Endicott