As we discuss Prince Caspian, you’ll find some background information about the book and C.S. Lewis in the Inspiration section available to all subscribers. Paid subscribers have access to the more specific discussion in the Application section.

Inspiration of “The Ancient Treasure House”

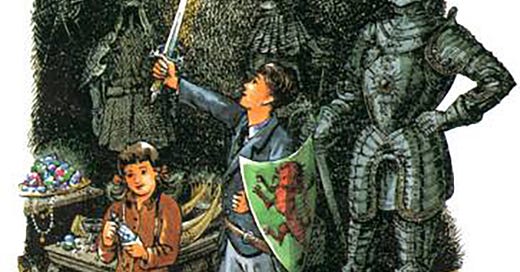

As the Pevensie children explore the “ancient treasure house” in the second chapter of Prince Caspian, C.S. Lewis notes how Susan pulled the string on her bow, and the resulting twang “vibrated through the whole room.” He says “that one small noise brought back the old days to the children’s minds more than anything that had happened yet. All the battles and hunts and feasts came rushing into their heads together.”

For someone often associated with the written word, Lewis was familiar with the power of sound and noises. He famously gave talks on BBC Radio that became the basis for Mere Christianity. Not only was he a popular lecturer at Oxford, but he also traveled and spoke to other groups. Lewis was also asked by MI6, the British spy agency famous for their fictional agent James Bond, to record a message for the people of Iceland. In it, he explained his love for Norse mythology and “northernness.”

Part of that love of all things Northern was sparked by an opera from the late 1800s. Richard Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen (or The Ring of the Nibelungs) provided one of the early stabs of “joy” that led to Lewis’ conversion years later and helped steep his mind in the fantastical.1

When he was around 13, Lewis first encountered the opera, but not by hearing it. Instead, he stumbled across illustrations by Arthur Rackham for an English-language translation of the text. In that moment, he felt that sudden fleeting pang of joy again, but as quickly as it flooded his mind, it vanished. “I knew (with fatal knowledge) that to ‘have it again’ was the supreme and only important object of desire,” Lewis says in Surprised by Joy. When much later, he finally heard a record of the Ride of the Valkyries, he said Rackham’s illustrations seemed to be “the very music made visible.”2

It may seem odd to devote attention to a 19th-century opera when discussing Narnia. Lewis himself recognized the unusual nature of devoting so many pages of his spiritual autobiography to his experience with Wagner, writing that some readers may feel it’s “undeserving” of the space he gives it. But he says he couldn’t continue any further with his life’s story before he discussed the seismic shift caused by his encounter with the opera.

As he delved deeper into Norse mythology, Lewis came to have an almost religious devotion to the gods of Asgard. He says he had an experience of “something very like adoration, some kind of quite disinterested self-abandonment to an object which securely claimed this by simply being the object it was.” Later, he recognizes this as a characteristic of God, one who is worthy of worship regardless of anything He has done for us. At that time, however, he says he came nearer to that feeling toward the Norse gods, in whom he did not believe, than he had previously done with the true God, when he had believed in Him.

For Lewis, however, this false god encounter was paving the way for something much greater. “Sometimes I can almost think that I was sent back to the false gods there to acquire some capacity for worship against the day when the true God should recall me to Himself,” he writes. J.R.R. Tolkien and Hugo Dyson would use mythology to help Lewis overcome his barriers to faith in God during their famous conversation on Addison’s Walk.

“Sometimes I can almost think that I was sent back to the false gods there to acquire some capacity for worship against the day when the true God should recall me to Himself.”

— C.S. Lewis, Surprised by Joy

Additionally, this love of northernness woke the imaginative pursuit in Lewis’ life. In his rational mind, he would move deeper into atheism and a rejection of God. In this imaginative side of his life, however, he would continue to long for joy. He recognized something was missing. It was just out of reach, but it was there. Later, he realized even that desire had meaning.

In Mere Christianity, he speaks of the innate desires that humans have for things like food and sex, and the natural existence of things that meet those desires. “If I find in myself a desire which no experience in this world can satisfy, the most probable explanation is that I was made for another world,” Lewis concludes. “If none of my earthly pleasures satisfy it, that does not prove that the universe is a fraud. Probably earthly pleasures were never meant to satisfy it, but only to arouse it, to suggest the real thing.”

In Prince Caspian, the children have a strange feeling about the place they found themselves, while they still long to be in Narnia. Lucy even suggests they pretend they are in Cair Paravel. Once again, the imagination can precede our rational mind. They don’t merely accept the imaginative possibility without using logic and tangible investigation, but their imagination helps lead them to the truth. For them (and us), truth is connected to identity.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Wardrobe Door to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.