“I expect you’ve seen someone put a lighted match to a bit of newspaper which is propped up in a grate against an unlit fire. And for a second nothing seems to have happened; and then you notice a tiny streak of flame creeping along the edge of the newspaper.”

Using an everyday analogy in “What Happened About the Statues,” C.S. Lewis helps readers picture the transformation of the lion statue back into a real lion after Aslan breathed on it. “Then a tiny streak of gold began to run along his white marble back—then it spread—then the color seemed to lick all over him as the flame licks all over a bit of paper …”

Yes, this works to describe the lion’s change, but there’s another layer to the analogy. The physical world picture helps us visualize the fantasy world events, and both give us a deeper understanding of what happens in the spiritual world with salvation.

In 1916, Lewis wrote to his friend Arthur Greeves: “I believe in no religion. There is absolutely no proof for any of them, and from a philosophical standpoint Christianity is not even the best.” He had become a committed atheist, but unbeknownst to him, sparks had been lit that would soon ignite a blaze in his heart.

C.S. Lewis announced himself a committed atheist in 1916, but unbeknownst to him, sparks had been lit that would soon ignite a divine blaze in his heart.

Lewis read George MacDonald’s Phantastes which “baptized his imagination.” Spark. G.K. Chesterton’s The Everlasting Man demonstrated that the Christian outline of history made more sense than the secular version. Spark. A fellow atheist spoke about the historicity of Gospel accounts and how the whole idea of a dying god “almost looks as if it had really happened once.” Spark.

Lewis, for his part, could feel the fires getting warmer. He wrote to Owen Barfield: “Terrible things are happening to me. The ‘Spirit’ or ‘Real I’ is showing an alarming tendency to become much more personal and is taking the offensive, and behaving just like God.” Much like the paper is not in control of the fire, Lewis recognized he was not much in control of this spiritual conversion process. “Amiable agnostics will talk cheerfully about ‘man’s search for God.’ To me, as then I was, they might as well have talked about the mouse’s search for the cat.”

As he sat in his room, “the most dejected and reluctant convert in all of England,” the flame were engulfing Lewis’ paper-mâché defenses. His conversation with J.R.R. Tolkien and Huge Dyson fanned the flame further. And on that faithful ride to Whipsnade Zoo, C.S. Lewis trusted in Christ for salvation. What set Lewis apart was that the fire continued to roar over all he was, as Walter Hooper described him as “the most thoroughly converted man.”

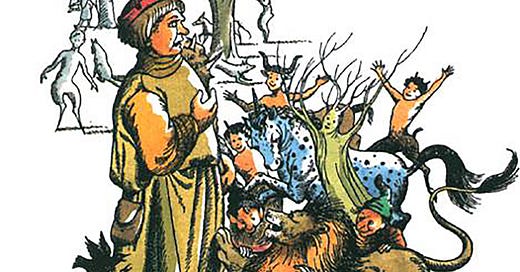

Similarly, what we see in this chapter are lives changed. As Aslan breaths on all the statues in the witch’s castle, they come to life in a blaze of colors and a symphony of sounds. Lewis gives us rich color details and a description of “happy roarings, brayings, yelpings, barkings, squealings, cooings, neighings, stampings, shouts, hurrahs, songs and laughter.”

The vibrant uniqueness of each newly reborn animal speaks to how Lewis’ describes our gaining our true personalities with God. “Sameness is to be found most among the most ‘natural’ men, not among those who surrender to Christ,” he writes in Mere Christianity. “How monotonously alike all the great tyrants and conquerors have been; how gloriously different are the saints.”

“How monotonously alike all the great tyrants and conquerors have been; how gloriously different are the saints.” — C.S. Lewis, “Mere Christianity”

Note all the distinct characters quickly introduced in this chapter: the lion delighted by Aslan saying “Us lions,” the kindly giant Rumblebuffin who almost uses Lucy as a handkerchief, the battle-ready centaur, and all the other individuals who may only show up for a brief moment but are treated as individuals with unique skills and personalities.

This “gloriously different” crowd of talking animals and mythical creatures burst out of the castle, with help from the friendly giant Rumblebuffin, and run to the battle. There they find Peter, Edmund and the rest of Aslan’s army bravely fighting back against a horde of creatures that looked to Lucy “even stranger and more evil and more deformed” in the daylight than they had the night before. But Aslan roars with such force that all of Narnia shakes, jumps on the witch, and ends the fight. The cat has found the mouse.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Wardrobe Door to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.